As a scholar of religion, I’m keenly aware that the humanities writ large are under attack. Constant defunding, vis a vie the corporitization of colleges and universities, means that the humanities dwindles into obscurity because it doesn’t easily translate into job marketability. It’s harder to guarantee that if you major in 19th century Russian literature you will run a Fortune-500 company by the time you are 26.

While I’m not interested in tailoring the humanities to the job market, I do think the strength of the humanities rests in the ability to impart critical thinking, researching, and writing skills to current and future generations of students. I believe these skills serve students no matter their individual vocational aspirations. Moreover, the ability to think critically, read critically, and write critically is imperative to the health of society as a whole. In an era of digital hyper-stimulation and rampant misinformation, it’s imperative that successive generations of students be able to discern fact from fiction, complex realities from popular oversimplifications.

As such, my courses are designed to foster these skills in each of my students.

In order to create an accessible learning environment, I do the following for each of my classes:

- I send weekly recap emails, summarizing what we’ve talked about and what it next on the horizon in terms of readings and assignments

- I upload all of the readings to the course website, and don’t require students to purchase books

- I strive to use plain language in writing assignment directions

- I go over the assignment directions in class, before the assignment is due

- I earmark time throughout the semester to teach my students academic reading, writing, and researching skills. While this may register as remedial, I do this with the full awareness that not assumed everyone comes in with those skill sets. It also establishes what I specifically expect in my courses as opposed to a nebulous generic standard of what college professors might expect that’s taught in high school.

In the classroom, I function as a facilitator. I don’t believe lengthy lectures are useful for the retention of information. Lengthy lectures are also not friendly to disabled or chronically ill students, let alone disabled/chronically ill professors like myself. Rather, I believe knowledge is embodied, which means students need to play an active role in generating collective knowledge. In each class, I come with questions or activities to generate the conversation. This allows for maximum student participation, regardless of whether a student has come “completely prepared” for the day’s session.

As far as assignments go, I believe that less is more and quality is better than quantity. I typically assign two to three synthesis papers per semester, which are 600 word essays written in response to prompts that are specific to the course’s unit. Synthesis papers function to teach students how to formulate a scholarly opinion rooted in deep readings of assigned materials. If a student receives a low grade and wants to strive for a higher grade, they are free to revise their synthesis paper in accordance with the extensive feedback I provide.

In my classes, synthesis papers pave the way for the final paper project, where students learn how to construct an inquiry of their choosing and follow it to completion. Final papers allow students to connect their interest in a subject to the world academic knowledge production. They get to experience academics who share their interest and explore it in interdisciplinary ways.

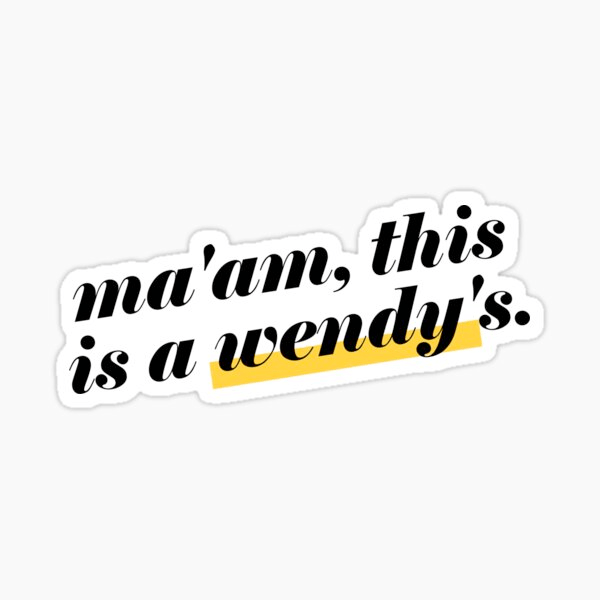

Overall, my teaching philosophy can aptly be described with the phrase “this is a wendys.”

(an image of a sticker on redbubble that reads “ma’am, this is a wendys.”)

When I tell my students “this is a wendy’s”, I’m telling them that they don’t have to fry their nervous systems in order to pass my class. I am not a professor who gets my kicks by torturing students in the unfortunate ways some of my professors tried to haze me. Unlike some of my colleagues, I have a life and better coping mechanisms than delighting in torturing students. I believe in transparency and mutual accountability, which can’t be fostered through power plays inside and outside the classroom.